|

(by Erin Burt)

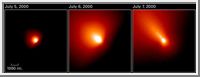

Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers

watching the comet LINEAR (C/1999 S4) in July 2000

were surprised to catch the icy comet in a brief,

violent outburst when it blew off a piece of its crust,

like a cork popping off a champagne bottle.

Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers

watching the comet LINEAR (C/1999 S4) in July 2000

were surprised to catch the icy comet in a brief,

violent outburst when it blew off a piece of its crust,

like a cork popping off a champagne bottle.

The eruption, the comet's equivalent of a volcanic

explosion, spewed a great deal of dust into space

(even though temperatures are far below freezing,

at about minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the icy regions

of the nucleus of core). This mist of dust reflected sunlight,

dramatically increasing the comet's brightness over

several hours. Hubble's sharp vision recorded the entire

event and even snapped a picture of the chunk of

material jettisoned from the nucleus and floating away

along the comet's tail. The renegade fragment moved away

from the core's weak gravitational grasp at an average

speed of about 6 mph.

Scientists have identified several theories for the

eruption. One possible reason is that a particularly

volatile region of the core became exposed to sunlight

for the first time and vaporized suddenly. Another

possibility is that a buildup of gas pressure from

sublimating ice (a change from ice to gas) trapped just

below the comet's surface explosively blew the lid off

a pancake-shaped layer of crust from its surface. The

pressure from sunlight blew the fragment down the tail.

Yet another possibility is that the observed fragment is

one of the house-sized "cometesimals" that are thought

to make up the nucleus. Evidence accumulated during the

past decade suggests that comet nuclei are "rubble

piles" of loosely held together cometseimals. Perhaps

one of the "building blocks" comprising the core broke

off and was blown down the tail by a gaseous jet

shooting off the comet's surface like a garden hose

spray.

Though comet nuclei have been known to fragment,

the view from the Hubble telescope is revealing finer

details of how they break apart. This unexpected glimpse

at a transitory event may indicate that these types of

"Mt. Saint Helens" outbursts occur frequently on the

comet.

The orbiting observatory's Space Telescope Imaging

Spectograph tracked the streaking comet from

July 5 to 7, capturing the leap in brightness and

discovering the castaway chunk of material sailing

along LINEAR's tail. When the Hubble telescope first

spied the comet 74 million miles from Earth, the icy

object's brightness rose by about 50 percent in less

than four hours. By the next day, the comet was 1/3

less luminous than it was the previous day, and on the

final day, the comet was back to normal.

A week later, on July 14, NASA's Chandra X-ray

Observatory imaged the comet and detected X-rays from

oxygen and nitrogen ions. The details of the X-ray

emission show that the comet produces X-rays due to the

exchange of electrons in collisions between nitrogen

and oxygen ions in the solar wind and electrically

neutral elements (predominantly hydrogen) in the

comet's atmosphere. To further examine these findings,

the comet LINEAR will be re-observed with Chandra from

July 29 - August 13, 2000.

A week later, on July 14, NASA's Chandra X-ray

Observatory imaged the comet and detected X-rays from

oxygen and nitrogen ions. The details of the X-ray

emission show that the comet produces X-rays due to the

exchange of electrons in collisions between nitrogen

and oxygen ions in the solar wind and electrically

neutral elements (predominantly hydrogen) in the

comet's atmosphere. To further examine these findings,

the comet LINEAR will be re-observed with Chandra from

July 29 - August 13, 2000.

Hubble observations of comet LINEAR also measured a

deficiency of carbon monoxide compared with other

comets, which suggests that the comet origianlly formed

much closer to the Sun at temperatures that would have

depleted the carbon monoxide. The comet was then tossed

out to the Oort cloud, a vast and distant "deep freeze"

reservoir of primordial comet nuclei.

Comet LINEAR is named for the observatory that

originally discovered it in September 1999. LINEAR is

the acronym for Lincoln Near Earth Asteroid Research,

a project based in Lexington, Massachusetts.