-

On Mars:

Exploration of the Red Planet. 1958-1978

-

-

-

- EVOLVING A CERTIFICATION

PROCESS

-

-

-

- [323] Along with radar and C site

problems, site certification remained an open issue. In late May

1975, the Viking Project Office released one of the major products

of the Landing Site Staff, a draft of the "Site A-1 Certification

Procedure." This document described how the landing specialists

would establish the acceptability of A-1 for landing and how they

would....

-

-

-

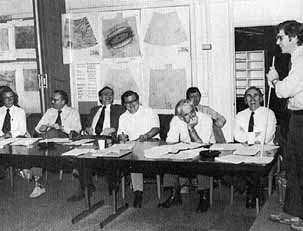

- During the 24 February 1975 landing

site working group meeting, Len Tyler explains his complex radar

studies of the Martian surface to (left to right) B. G. Lee,

William Michael, Thomas Mutch, Don Anderson, Richard Shorthill,

Gary Price, and Robert Hargraves.

-

-

- [324]....recommended a target point that

maximized the probability of a safe touchdown. Their

recommendations would be based primarily on their analyses of

low-altitude photographs taken during the first 10 orbiter

revolutions. Key to the certification process would be the

stereophotographic swaths of the A-1 site taken during the fourth

and sixth revolutions - called P4 and P6 photos, as the

revolutions were numbered from Viking's periapsides. After

playback on video recorders, reconstruction, image processing, and

enhancement, these photo frames, in the form of stereo pairs,

would be analyzed at the U.S. Geological Survey's Flagstaff

facility where ground elevation, slope angles. and surface

roughness would be estimated. This information would be used with

photo mosaics made from the orbiter frames to produce geologic

maps of the proposed landing site region. Earth-based radar and

telescopic observations, oblique and high-altitude photos, as well

as Mars atmospheric-water detector and infrared thermal- mapping

coverage of the landing site region, would provide supportive

information about the nature of the surface. From this data base,

landing site specialists would prepare a safety assessment report

of the target zone.

-

- During the site certification process, the

Landing Site Staff would provide a series of recommendations. Just

before the craft inserted into orbit of Mars, the team would

decide either to execute the normal insertion maneuver and proceed

with data acquisition or to modify the maneuver if a dust storm or

some other anomaly were detected during approach. After playback,

processing, and inspection of the imaging system frames from a

pass over the A-1 site, it might be necessary to adjust the timing

of the orbit or the pointing of the camera platform to obtain

optimum coverage of the site on subsequent passes. Four such

data-acquisition-adjustment opportunities were planned that would

affect the camera sequences at or near P3, P4, P6, and P10. The

Viking team would then have to answer the crucial question: would

it land the craft or reject the site the team had selected?

Recommendations would be made at three points before lander

separation from the orbiter. A preliminary commitment to A-I would

be made seven days before separation (at about P9), based on a

preliminary assessment of available data. A firm commitment to

land would be made three days later, and a precise target point

would be established. A final commitment to land, made just before

separation, would be determined after examining photos taken

during the previous five days to confirm the absence of dust

storms and high winds. 12

-

- In the time that remained before the

spacecraft reached Mars, the Landing Site Staff continued

extensive preparations for completing site certification and

lander release. In June and July, a functional test checked the

ground-based hardware that would process photos from the orbiter

and make the photomosaics and maps. The weakest link in the

several-hundred-million-kilometer chain from Mars to the photo

analysis labs in northern Arizona seemed to be the 850 kilometers

the photographs traveled across the western U.S. Continental

Trailways bus express, a leased army [325] aircraft and datafax

were used to strengthen connection between Los Angeles and

Flagstaff. The team did parts of the test a second time, verifying

the readiness of the processing equipment and the personnel.

13

-

- During the last months of 1975 and early

1976, the staff gave considerable attention to timing. Since so

much depended on timely certification, scheduling became a

paramount concern. The landing site specialists, working closely

with the mission design team and the orbiter performance and

analysis group, were ready by early February 1976 to test the

timeline in what they called the ``SAMPD- l'' test, an exercise

developed by B. Gentry Lee's Science Analysis and Mission Planning

Directorate. 14

-

-

-