|

|

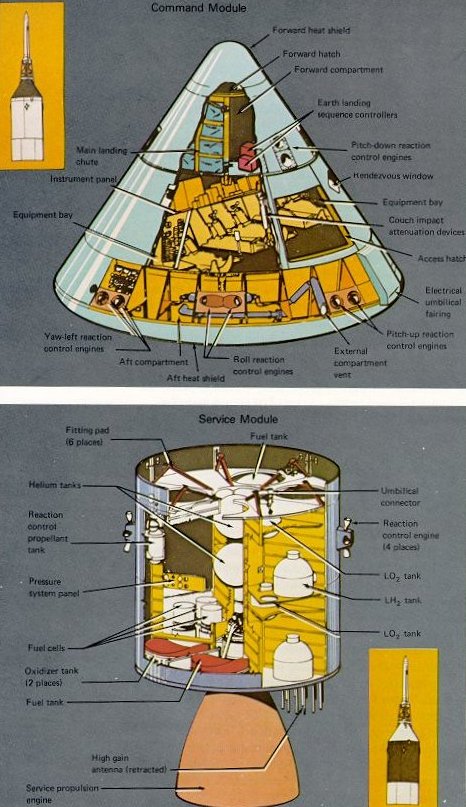

Above: Looking like a huge toy top

the conical command module

was crammed with some of

the most complex equipment

ever sent into space. The three

astronaut couches were surrounded by instrument panels,

navigation gear, radios, life-support systems, and small

engines to keep it stable during

reentry. The entire cone, 11

feet long and 13 feet in diameter, was protected by a

charring heat shield. The 6.5-ton CM was all that was

finally left of the 3000-ton

Saturn V stack that lifted oft

on the journey to the Moon.

Below: Packed with plumbing and tanks, the service module was the CM's constant companion until just before reentry. So all components not needed during the last few minutes of flight, and therefore requiring no protection against reentry heat, were transported in this module. It carried oxygen for most of the trip; fuel cells to generate electricity (along with the oxygen and hydrogen to run them); small engines to control pitch, roll, and yaw; and a large engine to propel the spacecraft into -and out of- lunar orbit. |

|

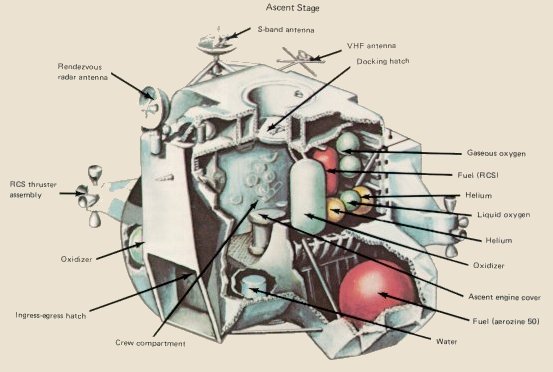

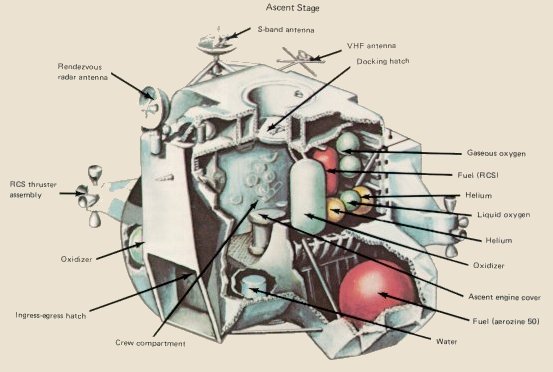

| The lunar module was also a two-part spacecraft. Its lower or descent stage had the landing gear and engines and fuel needed for the landing. When the LM blasted off the Moon, the descent stage served as the launching pad for its companion ascent stage, which was also home for the two explorers on the surface. In function if not in looks the LM was like the CM, full of gear to communicate, navigate, and rendezvous. But it also had its own propulsion system, an engine to lift it off the Moon and send it on a course toward the command module orbiting above. |

|

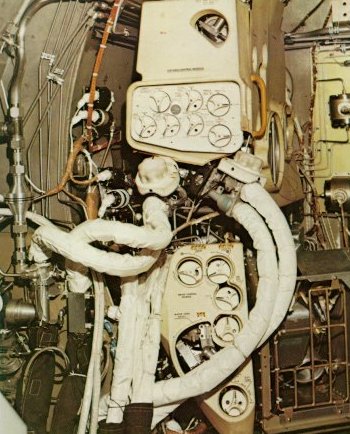

| Like a plumber's dream, the LM's environmental control system nestled in a corner of the ascent stage. Those hoses provided pure oxygen to two astronauts at a pressure one-third that of normal atmosphere, and at a comfortable temperature. The unit recirculated the gas, scrubbed out CO2 and moisture exhaled, and replenished oxygen as it was used up. |

|

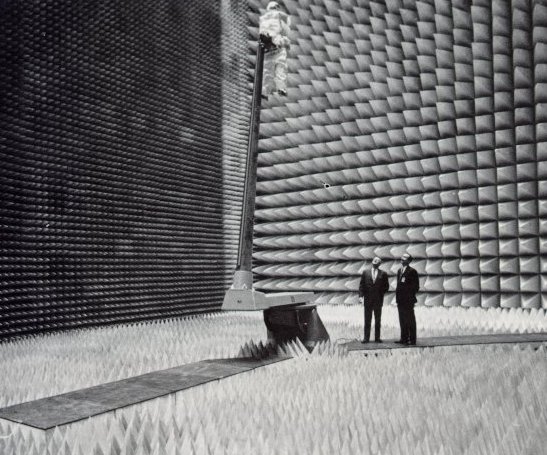

| Sound is deadened and not an echo can be heard in this anechoic test chamber. Used to simulate reflection-free space, its floor, walls, and ceiling are completely covered with foam pyramids that absorb stray radiation, so that an antenna's patterns can be accurately measured. Here two NASA engineers inspect a test setup of an astronaut's backpack. Any interference between the astronaut and his small antenna could be detected and fixed before a real astronaut set foot on the Moon. |

|

| Like new Magellans, astronauts learned to navigate in space. Here Walt Cunningham makes his observations through a spacecraft window. The tools of a space navigator included a sextant to sight on the stars, a gyroscopically stabilized platform to hold a constant reference in space, and a computer to link the data and make the most complex and precise calculations. |

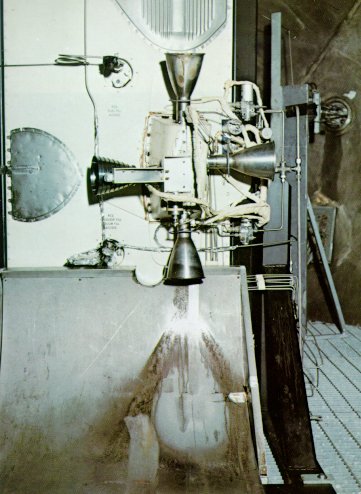

| Because there is no air to deflect, a spacecraft lacks rudders or ailerons. Instead, it has small rocket engines to pitch it up or down, to yaw it left or right, or to roll it about one axis. Sixteen of them were mounted on the service module, in "quads" of four. Here one quad is tested to make sure that hot rocket exhaust will not burn a hole in the spacecraft's thin skin. |

|

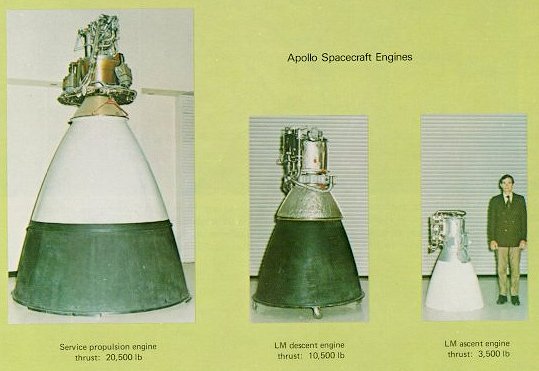

| Similar in shape but not size were the three big engines aboard Apollo spacecraft. Two of them had no backup, so they were designed to be the most reliable engines ever built. lf the service-propulsion engine failed in lunar orbit, three astronauts would be unable to return home; if the ascent engine failed on the Moon, it would leave two explorers stranded. (A descent-engine failure would not be as critical, because the ascent engine might be used to save the crew members.) |