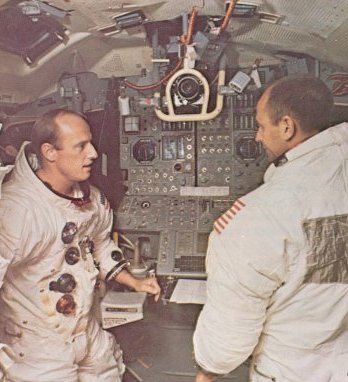

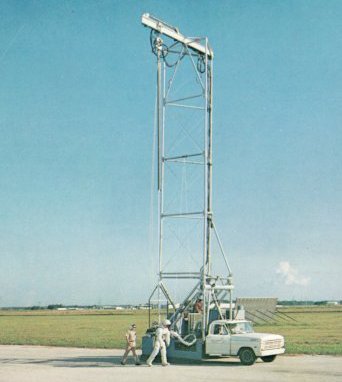

|

"The great train wreck" was John

Young's description of the contraption

beyond the console. At the top of the

stairs was a compartment that exactly

duplicated a command module control

area, with all switches and equipment.

Astronauts spent countless hours lying

on their backs in the CM simulator in

Houston. Panel lights came on and off,

gauges registered consumables, and

navigational data were displayed. Movie

screens replaced the spacecraft windows

and reflected whatever the computer

was thinking as a result of the combined

input from the console outside and

astronaut responses. Here the astronauts

practiced spacecraft rendezvous,

star alignment, and stabilizing a tumbling spacecraft.

The thousands of hours

of training in this collection of curiously

angled cubicles paid off. Many of the

problems that showed up in flight had

already been considered and it was

then merely a matter of keying in the

proper responses. At left (below), Charles Conrad

and Alan Bean in the LM simulator

at Cape Kennedy prepare to cope with

any possible malfunctions that the controllers at the console outside could

think up to test their familiarity with

the spacecraft and its systems.

|