|

|

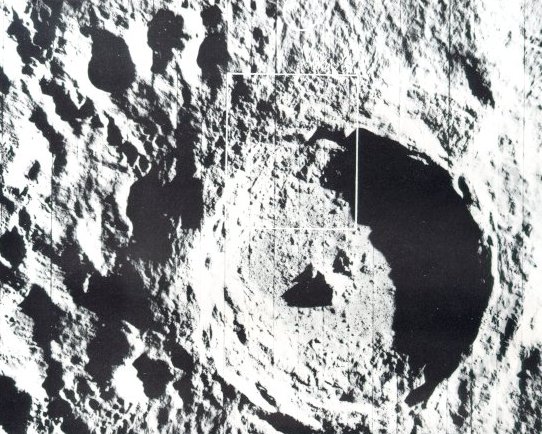

| The youngest big crater on the Moon is Tycho, which is about 53 miles across and nearly 3 miles deep. These Orbiter V photographs reveal its intricate structure. (Area in the rectangle above is pictured in higher resolution below.) A high central peak arises from the rough floor, and the crater wall has extensively slumped. The comparative scarcity of small craters within Tycho indicate its relatively recent origin. Flow features seen in both pictures could have been molten lava, volcanic debris, or fluidized impact-ejected material. Surveyor VII landed about 18 miles north of Tycho, in the area indicated by the white circle above. Enlargements of these pictures show an abundance of fissures and large fractured blocks, particularly near the uppermost wall scarp. |

|

|

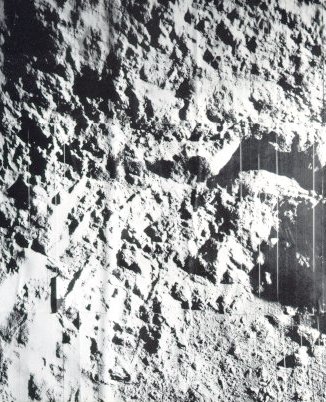

| This breath-taking view was one of Lunar Orbiter II's most captivating photographic achievements. For many people who had only seen an Earth-based telescopic view looking down into the crater Copernicus, this oblique view suddenly transformed that static lunar feature into a dramatic landscape with rolling mountains, sweeping palisades, and tumbling land-slides. The crater Copernicus is about 60 miles in diameter, 2 miles deep, with 3000-foot cliffs. Peaks near the center of the crater form a mountain range about 10 miles long and 2000 feet high. Lunar Orbiter II recorded this "picture of the year" on November 28, 1964, from 28.4 miles above the surface when it was about 150 miles due south of the crater. |

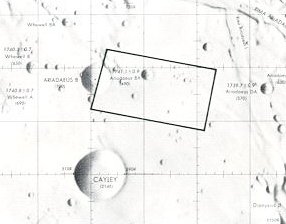

| The best maps weren't good enough, even though they were based an years of telescopic photography from Earth. In early planning, the rectangle in the map at left was a possibility os a landing site. The handful of craters shown, it was innocently thought, should be easy enough to dodge during the last moments of a piloted landing. The site was an 11- by 20-mile rectangle located in the highlands west of Mare Tranquillitatis. |

|

| The truth about this site was revealed by the accurate eye of Lunar Orbiter II: it was far too rough to be attempted in an early manned landing. In fact, Orbiter pictures showed that parts of the Moon were as rough as a World War I battlefield, with craters within craters, and all parts of the surface tilled and pulverized by a rocky rain. No areas were found smooth enough to meet the original Apollo landing-site criteria, but a few approached it and the presence of a skilled pilot aboard the LM to perform last-minute corrections mode landings possible. The high-quality imagery returned by the Orbiters also returned a harvest of new scientific information. |

|

|

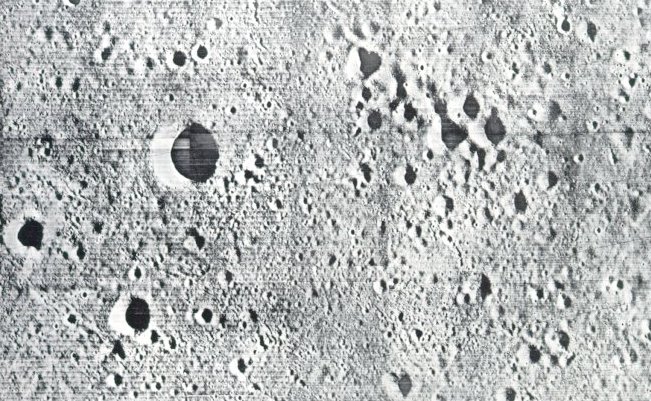

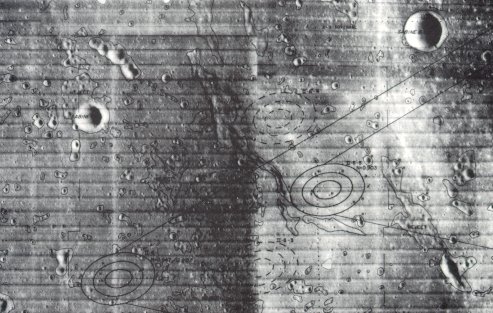

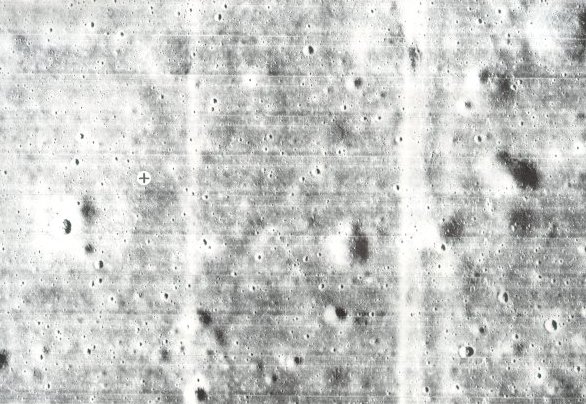

A typical marked mosaic is reproduced above. It is a view of a

region in Mare Tranquillitatis, and

the area within the set of ellipses

at the far left was chosen as the

target for the first manned landing.

Before it was selected, high-resolution Orbiter Photos were used to

examine details within the landing

ellipses. In those Photos surface

irregularities as small as 3 feet

could be seen. One such mosaic is

reproduced below.

The black cross in a white circle marks the spot where the Apollo 11 astronauts' landing module descended. It was in an elliptical target area only 200 feet wide. |

|

|

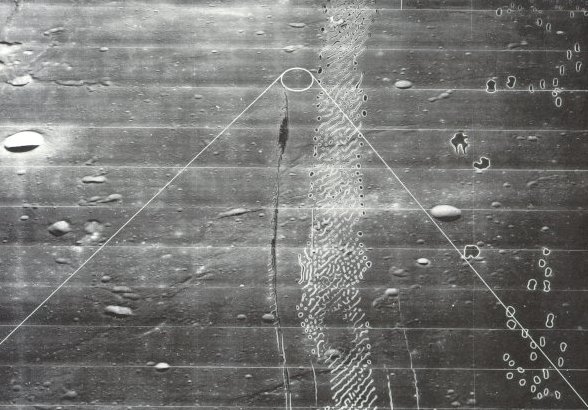

| The picture above is an oblique view of the same area. This Lunar Orbiter photograph illustrates more nearly the way it would look to an astronaut descending to land. The white lines iridicate the elliptical target site and the approach boundaries. Processing flaws such as seen in this picture resulted occasionally from partial sticking of the moist bimat film development used aboard the Orbiter spacecraft. |