|

|

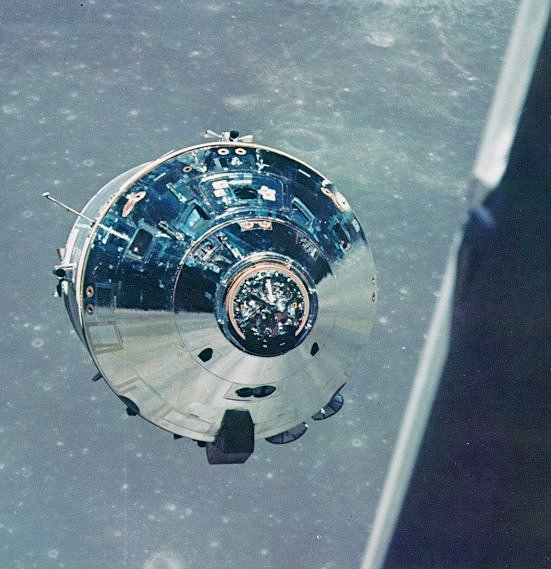

| Glistening in the sunlight, reflecting the Moon in bright metal as yet undarkened by the savage heat of atmospheric reentry, the Apollo 10 command module ghosts silently within a few yards of its lunar module, occupied by Gene Cernan and Tom Stafford. John Young is alone in the command module at this point. The background is the far side of the Moon, about 60 miles down. |

| Shaving in space, expected to be a problem (neither astronauts nor delicate mechanism would thrive in a whiskery atmosphere), proved to be no problem at all with an adequately sticky lather. Looking on is Apollo 10 Commander Stafford. |

| A meal, not a map, is what Gene Cernan is holding up here. It's a plastic envelope containing a chicken and vegetabie mix; und with hot water added it made a palatable main course. In the Mercury days space food had been almost as grim as Army survival rations, but during Apollo the eating grew a lot better. By the end of the program, individual astronaut preferences were reflected in the flight menus, and spooned dishes and sandwich spreads were available. |

|

| Manning his control console in the Mission Control Center in Houston is George M. Low, then Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager. Behind him is Chris Kraft, Director of Flight Operations at the Manned Spacecraft Center. They and the other men in the photo are viewing a color television transmission from the Apollo 10 during the second day of ist lunar orbit mission. The spacecraft at this point was some 112,000 miles from the Earth, about halfway to the Moon. Low's TV monitor is off to the left. |

|

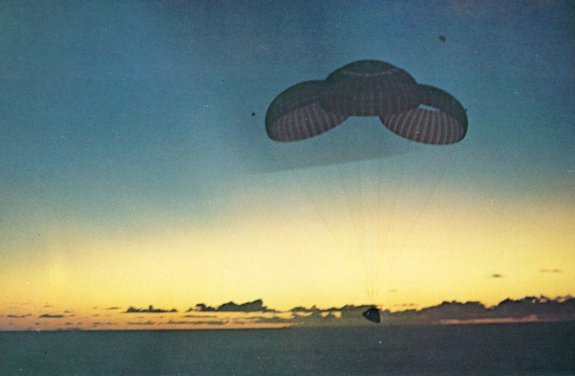

| Dawn was just breaking as Apollo 10 gently floated down into the Pacific 395 miles east of Pago Pago. The pinpoint landing was so accurate that the blinking tracking lights on the spacecraft were visible from the USS Princeton during the descent. |

| Flotation collar secured, frogmen get ready to assist the Apollo 10 astronauts from the command module. Named Charlie Brown, the CM landed three and a half miles from the USS Princeton. About one-half hour later the astronauts were aboard the recovery ship, having spent eight days in space. |

| Returning from the dress rehearsal, Commander Thomas P. Stafford is aided from the command module by frogmen. By demonstrating lunar orbit rendezvous and the LM descent system, this lunar orbit mission set the stage for Apollo 11, which flew two months later and put men on the Moon. |

| Hoist away! Shortly after they come down from space, the astronauts go back up; this time only briefly as the cage and sling carry them one at a time to the recovery helicopter hovering above (the camera freezes two of its blades). |

| Glad to be horne. Standing in the 'copter doorway the jubilant Apollo 10 crew smile at well-wishers aboard the Princeton. From left: LM Pilot Gene Cernan, Commander Tom Stafford, and CM Pilot John Young. The Apollo 10 splashdown was near American Samoa. |