|

COMETS EARTH JUPITER KUIPER BELT MARS MERCURY METEORITES NEPTUNE OORT CLOUD PLUTO SATURN SOLAR SYSTEM SPACE SUN URANUS VENUS ORDER PRINTS

PHOTO CATEGORIES SCIENCEVIEWS AMERICAN INDIAN AMPHIBIANS BIRDS BUGS FINE ART FOSSILS THE ISLANDS HISTORICAL PHOTOS MAMMALS OTHER PARKS PLANTS RELIGIOUS REPTILES SCIENCEVIEWS PRINTS

|

Related Document

Download Options

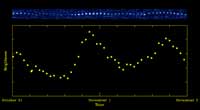

The upper panel of this figure shows small images of the comet, specially filtered to show only carbon dioxide, or evaporated dry ice, as a function of time (shown at the bottom). The brightness varies dramatically from one image to another, which means that the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by the comet is varying up and down. A close look at the images shows that the position of the carbon dioxide also varies by a small amount, up and down in the pictures, just as the brightness varies. The lower panel is a graph showing the variation of total brightness, and thus the variation of the total amount of carbon dioxide, during the time period. The amount of carbon dioxide emitted very late on Oct. 31 is more than four times greater than earlier on that same day. During this same period of two days, the water (not shown) varied much less than the carbon dioxide. This suggests that some chunks of the comet's nucleus have much more dry ice relative to water than do other chunks. Carbon dioxide is a basic ingredient of comets and planets in our solar system. Scientists on the EPOXI team think that sunlight is warming the comet, causing its frozen, sub-surface carbon dioxide to bubble up into gas that is escaping in jets. These data were collected by EPOXI's infrared spectrometer, part of its High-Resolution Instrument. |