|

COMETS EARTH JUPITER KUIPER BELT MARS MERCURY METEORITES NEPTUNE OORT CLOUD PLUTO SATURN SOLAR SYSTEM SPACE SUN URANUS VENUS ORDER PRINTS

PHOTO CATEGORIES SCIENCEVIEWS AMERICAN INDIAN AMPHIBIANS BIRDS BUGS FINE ART FOSSILS THE ISLANDS HISTORICAL PHOTOS MAMMALS OTHER PARKS PLANTS RELIGIOUS REPTILES SCIENCEVIEWS PRINTS

|

Related Documents

Download Options

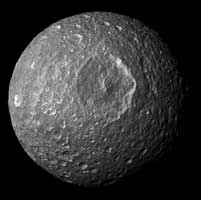

This mosaic, created from images taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft during its closest flyby of Saturn's moon Mimas, looks straight at the moon's huge Herschel Crater and reveals new insights about the moon's surface. Bright-walled craters, with floors and surroundings about 20 percent darker than the steep crater walls, are notable in this view. Mimas' original surface, like the surfaces of most of the other major Saturnian moons without atmospheres, is not pure ice but contains some dark impurities. Herschel Crater (130 kilometers, 80 miles wide) and some of the smaller craters seen in this mosaic show relatively dark markings along the lower portion of their crater walls (marked in green in the annotated version of the image). Cassini scientists interpret this darkening as evidence for the gradual concentration of impurities from evaporating icy materials in areas where the dark impurities slide slowly down the crater wall. There, bright ice is baked away by the sun and the vacuum of space. At Herschel, the edge where the darker regions contact the crater floor is interrupted by an extensive hummocky area. Scientists believe the hummocky texture came from the flow of melted ice that occurred during the impact that created the crater. That melt filled the bottom of the crater around the central peak. Dark streaks are seen making their way down the sides of some craters (marked red in the annotated version), often originating from pockets of dark contaminants embedded just below the rim of the crater wall. The pockets themselves likely represent small, pre-existing, dark-floored craters that were buried by the blanket of material that was thrown out from the newer impact that created the crater rim. The material from a newly exposed dark layer eventually moves downslope and forms a streak. Streaks are sometimes seen starting from the floors of smaller, dark-floored craters perched along rims of larger craters. The interior of Herschel Crater is significantly less cratered than the continuous blanket of ejected material that extends radially outward from its rim. The violent meteor impact that excavated Herschel blasted pulverized debris, including massive chunks of ice, upward. The fallback of this ejected material over the crater rim created a thick debris blanket and dotted it with secondary craters. The presence of a fluid pool of melted material on the crater floor, which solidified after the debris fell, probably explains the relative absence of craters on Herschel's floor. These are common processes that should occur on bodies without atmospheres throughout the solar system. They may be accentuated on Mimas because of the large size of Herschel in comparison to Mimas' size. Cassini scientists also continue to study a color anomaly on Mimas. See PIA12572 and PIA06257 to learn more. Cassini came within about 9,500 kilometers (5,900 miles) of Mimas during its flyby on Feb. 13, 2010. This mosaic was created from seven images taken that day in visible light with Cassini's narrow-angle camera. An eighth image, taken with the wide-angle camera on the same flyby, is used to fill in the lower right of the mosaic. The images were re-projected into an orthographic map projection. This view looks toward the hemisphere of Mimas that leads in its orbit around Saturn. Mimas is 396 kilometers (246 miles) across. This view is centered on terrain at 10 degrees south latitude, 125 degrees west longitude. North is up. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 30,000 kilometers (19,000 miles) from Mimas and at a sun-Mimas-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 27 degrees. Image scale is 180 meters (600 feet) per pixel. |