Jupiter II

Freedom lies in being bold. - Robert Frost

|

Europa Introduction |

|

Parent Planet |

|

Europa Science |

Europa [yur-ROH-pah] is a unique moon of Jupiter that has fascinated scientists for hundreds of years. Its surface is among the brightest in the solar system, a consequence of sunlight reflecting off a relatively young icy crust. Its face is also among the smoothest, lacking the heavily cratered appearance characteristic of Callisto and Ganymede. Lines and cracks wrap the exterior as if a child had scribbled around it. Europa may be internally active, and its crust may have, or had in the past, liquid water which can harbor life.

Europa is named after the beautiful Phoenician princess who, according to Greek mythology, Zeus saw gathering flowers and immediately fell in love with. Zeus transformed himself into a white bull and carried Europa away to the island of Crete. He then revealed his true identity and Europa became the first queen of Crete. By Zeus, she mothered Trojan war contemporaries Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Sarpedon. Zeus later re-created the shape of the white bull in the stars which is now known as the constellation Taurus.

The fascination with Europa began centuries ago in 1610 when Galileo Galilei discovered four Jovian satellites: Io, Callisto, Ganymede, and Europa. But only recently have we begun to learn more about the sphere. About forty years ago, modern astronomer Gerard Kuiper and others showed that Europa's crust was composed of water and ice. In the 1970s, space exploration of Jupiter's satellite system began with the Pioneer and Voyager fly-by missions which verified Kuiper's analysis of Europa and discovered other characteristics. In 1995, the Galileo spacecraft began gathering more detailed images and measurements within the system, providing the information needed to piece together Europa's past, present, and future.

| Europa Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Simon Marius & Galileo Galilei |

| Date of discovery | 1610 |

| Mass (kg) | 4.8e+22 |

| Mass (Earth = 1) | 8.0321e-03 |

| Equatorial radius (km) | 1,569 |

| Equatorial radius (Earth = 1) | 2.4600e-01 |

| Mean density (gm/cm^3) | 3.01 |

| Mean distance from Jupiter (km) | 670,900 |

| Rotational period (days) | 3.551181 |

| Orbital period (days) | 3.551181 |

| Mean orbital velocity (km/sec) | 13.74 |

| Orbital eccentricity | 0.009 |

| Orbital inclination (degrees) | 0.470 |

| Escape velocity (km/sec) | 2.02 |

| Visual geometric albedo | 0.64 |

| Magnitude (Vo) | 5.29 |

See also: Additional Galileo Images of Europa.

Europa

Europa

This is one of the highest resolution images of Europa obtained by

Voyager 2.

It shows the smoothness of most of the terrain and the near absence

of impact craters. Only three craters larger than 5 km in diameter have

been found.

(Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

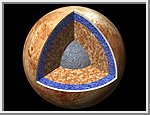

The Interior of Europa

The Interior of Europa

This cutaway view shows the possible internal structure of

Europa. It was created by using a mosaic of images obtained in

1979 by NASA's Voyager spacecraft. The interior characteristics are

inferred from gravity field and magnetic field measurements by the

Galileo spacecraft. Europa's radius is 1565 km, not too much smaller than

our Moon's radius. Europa has a metallic (iron, nickel) core (shown in

gray) drawn to the correct relative size. The core is surrounded by a

rock shell (shown in brown). The rock layer of Europa (drawn to correct

relative scale) is in turn surrounded by a shell of water in ice or

liquid form (shown in blue and white and drawn to the correct relative

scale). The surface layer of Europa is shown as white to indicate that it

may differ from the underlying layers. Galileo images of Europa suggest

that a liquid water ocean might now underlie a surface ice layer several

to ten kilometers thick. However, this evidence is also consistent with

the existence of a liquid water ocean in the past. It is not certain if

there is a liquid water ocean on Europa at present.

(Copyright 1999 by Calvin J. Hamilton)

Europa - The Past and Future

Europa - The Past and Future

This artistic picture represents Europa

during the dawn of the Solar System's creation.

At this point, in time oceans graced the surface of Europa.

Since liquid water existed in the past,

could life have formed and even exist today? The primary

ingredients for life are water, heat,

and organic compounds obtained from comets and meteorites.

Europa has had all three. From the images and data collected

by the Galileo spacecraft, scientists believe that a subsurface

ocean existed in relative recent history and may still be present

beneath the icy surface. Europa's water should have frozen long

ago, but warming could be occurring due to the tidal tug of

war with Jupiter and neighboring moons.

This artistic picture can also represent Europa 7 billion years

hence, after the Sun has become a red giant. The heat from the

aging sun should be sufficient to melt the ice and once again

produce an ocean.

(Copyright 1998 by Calvin J. Hamilton)

Europa From a Distance

Europa From a Distance

This view of Europa was taken by Voyager 2 and shows a bright,

low-contrast surface with a network of lines which crisscross much

of its surface.

(Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

Ridges on Europa

Ridges on Europa

This view of Europa shows a portion of the surface that

has been highly disrupted by fractures and ridges. This picture covers

an area about 238 kilometers (150 miles) wide by 225 kilometers (140

miles), or about the distance between Los Angeles and San Diego.

Symmetric ridges in the dark bands suggest that the surface crust was

separated and filled with darker material, somewhat analogous to

spreading centers in the ocean basins of Earth. Although some impact

craters are visible, their general absence indicates a youthful

surface. The youngest ridges, such as the two features that cross the

center of the picture, have central fractures, aligned knobs, and

irregular dark patches. These and other features could indicate

cryovolcanism, or processes related to eruption of ice and gases.

This picture, centered at 16 degrees south latitude, 196 degrees west

longitude, was taken at a distance of 40,973 kilometers (25,290 miles) on

November 6, 1996 by the solid state imaging television camera

onboard the Galileo spacecraft

during its third orbit around Jupiter.

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Natural and False Color Views of Europa

Natural and False Color Views of Europa

This image shows two views of the trailing hemisphere

of Europa. The left image shows the

approximate natural color appearance of Europa. The image on the right is

a false-color composite version combining violet, green and infrared

images to enhance color differences in the predominantly water-ice crust

of Europa. Dark brown areas represent rocky material derived from the

interior, implanted by impact, or from a combination of interior and

exterior sources. Bright plains in the polar areas (top and bottom) are

shown in tones of blue to distinguish possibly coarse-grained ice (dark

blue) from fine-grained ice (light blue). Long, dark lines are fractures

in the crust, some of which are more than 3,000 kilometers (1,850 miles)

long. The bright feature containing a central dark spot in the lower third

of the image is a young impact crater some 50 kilometers (31 miles) in

diameter. This crater has been provisionally named 'Pwyll' for the Celtic

god of the underworld.

(Courtesy DLR)

False Color Image of Minos Linea Region

False Color Image of Minos Linea Region

False color has been used here to enhance the

visibility of certain features in this composite of three images of the

Minos Linea region on Jupiter's moon Europa taken on 28 June 1996

Universal Time by the Galileo

spacecraft. Triple bands, lineae and mottled terrains appear in brown and

reddish hues, indicating the presence of contaminants in the ice. The icy

plains, shown here in bluish hues, subdivide into units with different

albedos at infrared wavelengths probably because of differences in the

grain size of the ice. The composite was produced using images with

effective wavelengths at 989, 757, and 559 nanometers. The spatial

resolution in the individual images ranges from 1.6 to 3.3 kilometers (1

to 2 miles) per pixel. The area covered, centered at 45N, 221 W, is about

1,260 km (about 780 miles) across.

(Courtesy NASA/AMES)

Galileo Near-Infrared Image of Europa

Galileo Near-Infrared Image of Europa

The Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) on the

Galileo spacecraft imaged most of Europa, including the north polar

regions, at high spectral resolution at a range of 156,000 km (97,500

miles) during the G1 encounter on June 28 1996. The image on the right

shows Europa as seen by NIMS, centered on 25 degrees N latitude, 220 W

longitude. This is the hemisphere that always faces away from Jupiter. The

image on the left shows the same view point from the Voyager data (from

the encounters in 1979 and 1980). The NIMS image is in the 1.5 micron

water band, in the infrared part of the spectrum. Comparison of the two

images, infrared to visible, shows a marked brightness contrast in the

NIMS 1.5 micron water band from area to area on the surface of Europa,

demonstrating the sensitivity of NIMS to compositional changes. NIMS

spectra show surface compositions ranging from pure water ice to mixtures

of water and other minerals which appear bright in the infrared.

Europa's Broken Ice

Europa's Broken Ice

Jupiter's moon Europa, as seen in this image taken June 27, 1996 by NASA's

Galileo spacecraft, displays features in some areas resembling ice floes seen in

Earth's polar seas. Europa has an icy crust

that has been severely fractured, as indicated by the dark linear, curved, and

wedged-shaped bands seen here. These fractures have broken the crust into

plates as large as 30 kilometers (18.5 miles) across. Areas between the plates

are filled with material that was probably icy slush contaminated with rocky

debris. Some individual plates were separated and rotated into new positions.

Europa's density indicates that it has a shell of water ice as thick as 100

kilometers (about 60 miles), parts of which could be liquid. Currently, water

ice could extend from the surface down to the rocky interior, but the features

seen in this image suggest that motion of the disrupted icy plates was

lubricated by soft ice or liquid water below the surface at the time of

disruption.

This image covers part of the equatorial zone of Europa and was taken from a

distance of 156,000 kilometers (about 96,300 miles) by the solid-state imager

camera on the Galileo spacecraft. North is to the right and the sun is nearly

directly overhead. The area shown is about 360 by 770 kilometers (220-by-475

miles or about the size of Nebraska), and the smallest visible feature is about

1.6 kilometers (1 mile) across.

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Europa's Active Surface

Europa's Active Surface

A newly discovered impact crater can be seen just right of the center of this

image of Jupiter's moon Europa returned by NASA's Galileo spacecraft camera.

The crater is about 30 kilometers (18.5 miles) in diameter. The impact

excavated into Europa's icy crust, throwing debris (seen as whitish material)

across the surrounding terrain. Also visible is a dark band, named Belus Linea,

extending east-west across the image. This type of feature, which scientists

call a "triple band," is characterized by a bright stripe down the middle.

The outer margins of this and other triple bands are diffuse, suggesting that the

dark material was put there as a result of possible geyser-like activity which shot

gas and rocky debris from Europa's interior. The curving "X" pattern seen in the

lower left corner of the image appears to represent fracturing of the icy crust

and infilling by slush which froze in place.

The crater is centered at about 2 degrees north latitude by 239 degrees west

longitude. The image was taken from a distance of 156,000 kilometers (about

96,300 miles) on June 27, 1996, during Galileo's first orbit around Jupiter.

The area shown is 860 by 700 kilometers (530 by 430 miles), or about the size

of Oregon and Washington combined.

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Dark Bands on Europa

Dark Bands on Europa

Dark crisscrossing bands on Jupiter's moon Europa represent widespread

disruption from fracturing and the possible eruption of gases and rocky

material from the moon's interior in this four-frame mosaic of images

from NASA's Galileo spacecraft. These and other features suggest that

soft ice or liquid water was present below the ice crust at the time of

disruption. The data do not rule out the possibility that such

conditions exist on Europa today. The pictures were taken from a

distance of 156,000 kilometers (about 96,300 miles) on June 27, 1996.

Many of the dark bands are more than 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles)

long, exceeding the length of the San Andreas fault of California.

Some of the features seen on the mosaic resulted from meteoritic

impact, including a 30-kilometer (18.5 mile) diameter crater visible as

a bright scar in the lower third of the picture. In addition, dozens

of shallow craters seen in some terrains along the sunset terminator

zone (upper right shadowed area of the image) are probably impact

craters. Other areas along the terminator lack craters, indicating

relatively youthful surfaces, suggestive of recent eruptions of icy

slush from the interior. The lower quarter of the mosaic includes

highly fractured terrain where the icy crust has been broken into slabs

as large as 30 kilometers (18.5 miles) across.

The mosaic covers a large part of the northern hemisphere and includes the north pole at the top of the image. The sun illuminates the surface from the left. The area shown is centered on 20 degrees north latitude and 220 degrees west longitude and is about as wide as the United States west of the Mississippi River. (Courtesy USGS Flagstaff)